Last month the National Catholic Register had a wonderful interview with Dawn Eden. It deeply touched my heart because although I have never suffered that kind of abuse someone very close to me did. She confided in me and I witnessed first hand her despair transform into God’s healing power. Since then my heart has a special place for others who have suffered such abuse. This is such an important topic instead of just giving the link I am reposting the interview here.

Most Catholics are already familiar with the name Dawn Eden, the rock-journalist-turned-devout-Catholic who made a splash with her bestselling book The Thrill of the Chaste. Eden has gone on to be a highly sought-after speaker and writer, especially on the subjects of chastity and human sexuality. Eden holds a master’s degree in theology and currently lives in Washington, where she’s studying toward a doctorate.

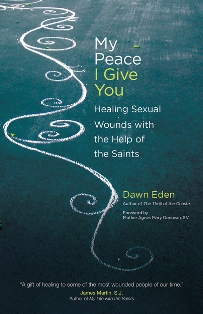

Her new book, My Peace I Give You, delves into the subject of childhood sexual abuse. She recently spoke with Jennifer Fulwiler about woundedness, healing and — for the first time publicly — her personal experience with this subject.

Your last book, The Thrill of the Chaste, was also on the subject of sexuality. How did My Peace I Give You develop from that one?

With The Thrill of the Chaste, I went public about my experience of conversion of life — receiving Christian faith and, with it, the desire to forgo a worldly lifestyle in favor of practicing chastity. I wanted readers to see that the virtue of chastity is intrinsically connected with life in Christ and that life in Christ is always joyful. So, although the book was marketed as a kind of “how to” on waiting until marriage, I actually saw chastity as a kind of hook to help people discover Christian joy.

Once I started speaking about The Thrill of the Chaste, people started coming to me with their problems and asking for my advice. I noticed that those who were in the most agony as they tried to live out Church teachings on chastity were very often people who had suffered abuse, particularly childhood sexual abuse.

Why do you think that is? What is it about being a victim of abuse that could lead to difficulty with chastity and other aspects of having a healthy relationship with sexuality?

I think that people who were sinned against sexually are much more conscious of lustful thoughts — by which I don’t mean simple feelings of attraction, which are not sinful in themselves, but lustful fantasies and the like — because they knew where those thoughts lead. They know what it’s like to have someone see them as an object of use. They understand that their abuse didn’t begin with the abuser’s physical sin against them, but earlier, when the abuser began to conceive of them as an object for his or her own pleasure.

Is childhood sexual abuse an issue with which you have personal experience?

Yes. After I entered into full communion with the Catholic Church in 2006, a part of the spiritual growth process for me was coming to terms with my experience of childhood sexual abuse. When writing The Thrill of the Chaste, I consciously knew that I had had those experiences — they were not repressed memories — but I had not “written” them in my mind as abuse.

It’s a very common experience of abuse victims, particularly those who experienced childhood sexual abuse, to fail to mentally categorize what was done to them as “abuse.” For various reasons that I go into in My Peace I Give You, children tend to blame themselves for what was done to them, as a psychological safety mechanism at the time of abuse.

Did these experiences of abuse create obstacles for your ability to find and come to know God?

Yes, I would say that the abuse that I underwent in childhood really made it extraordinarily difficult for me to discover the love of God.

Each of us has an individual identity given to us by God, our Father. Ordinarily, the child first discovers his identity by being beloved by his own parents. Then, having learned what a father is, what a mother is, and what it is to be loved and protected and sustained by his parents, the child learns there is a Father in heaven who loves him. Though the child’s identity is not created by his father and mother, he discovers his identity as a child of God through them. Without the love and protection of a stable family, it becomes very hard — not at all impossible, but very hard — to find your identity as a beloved child of God.

To be clear, I am not saying I was an utterly unloved child. But protection is part of love, and I was not protected as I should have been.

How did your conversion change that?

Partly through the help of a Catholic therapist, but largely thanks to going deeper into the Catholic spiritual life, with the help of confessors and a spiritual director, I started to confront the effects of abuse within myself and bring all those experiences to Christ.

One thing that came out of that was the need to be able to locate my own experiences within the experiences of the Church.

I didn’t want to feel as if the things I had suffered were completely outside God’s providence. Because I’m now a member of the mystical body of Christ, everything I’ve suffered is also part of the sufferings of the body of Christ.

God didn’t positively will the evil that was done to me, but he permitted me to suffer it — for the same reason he permits any evil: because he could bring from it a greater good. I realized I couldn’t change the past — not even God can do that. But I could find meaning in my past sufferings now that my life had become “hidden with Christ in God,” as St. Paul says. The lives of the saints were tremendously helpful in this regard, because each saint magnifies a different aspect of Christ’s life and of his suffering.

Abuse victims are sometimes resistant to seeking healing because they fear that it will involve reliving traumatic memories. Is that a necessary step for finding peace in Christ?

It’s very important to distinguish between what are appropriate psychological methods of healing to be done under the care of a qualified mental-health professional and what are appropriate spiritual approaches to healing. For example, for victims of post-traumatic stress disorder, there is a type of psychotherapy whereby a person relives certain traumatic experiences. For some people, that can be therapeutic. However, if done outside of a controlled setting with a medically qualified practitioner, it can be dangerous.

Moreover, there is a theological problem with telling people that Christ can only heal you if you relive each memory. You can see this when you look at how he heals people in the Gospels. When Jesus healed the leper in Galilee, did he touch every single part of the leper’s body? Of course not. The leper said to him in faith, “If you will, you can make me clean.” Jesus simply stretched out his hand and touched him, saying, “I will; be clean.”

The message in the Gospels is that our wounds are cracks where Christ’s light can get in. When we open ourselves to his healing light, we can trust in faith that he’ll reach all those dark places. Whether or not I can consciously remember every single thing that was done to me, all those experiences contributed in some way to who I am today. So when I offer my whole self to Christ, and ask him to enter in, I am asking Christ’s precious blood to bleed into all my past. Carrying that image of the Precious Blood and the light of Christ entering into my entire life is much more beautiful than trying to force myself to review every single wound.

You make an interesting point when you say that you felt “impure” because of what had been done to you; you realize, now, that you were “impure,” but not because of what happened in your childhood, but because of misguided actions you took to deal with the trauma later in life. Do you think this is common for victims of abuse?

I think it’s extremely common. During my teenage years and young adulthood, not having yet come to terms with the abuse, I was engaged in a search for identity and seeking it in things that were not of God. And I kept digging myself in deeper, thinking I was going to find myself through all kinds of rebellion, including sexual rebellion. I desperately wanted to be loved, but was convinced I was only lovable for what I did for other people and not for who I was.

For me, being able to seek healing from the effects of the child sexual abuse tied in with learning how to stop acting from the pathology of the wounded child and to start acting from the health that Christ was offering me.

Before your conversion, you went to a top psychiatrist in New York City, yet he failed to diagnose your post-traumatic stress disorder. How did secular society’s views of human sexuality impact that misdiagnosis?

He was following an overwhelmingly common belief among psychiatric professionals, which states that self-actualization can come through sexual activity, regardless of whether that activity is within marriage or a relationship. So the things I was doing that I now realize were damaging he saw as signs of health. He didn’t realize that I was acting out of my sickness and not out of my wellness.

Do you think that secular culture’s confusion about sexuality also impacts the way mental-health professionals identify and diagnose cases of abuse?

Yes. From my own experience, I personally believe that the emergence of the divorce culture, which started back in the 1950s and exploded during the 1960s and ’70s, lowered the bar in terms of what psychologists thought was an acceptable environment for children.

Before then, it was understood that children should be insulated from having to witness certain kinds of sexual behavior that are de rigueur now. I’m thinking, for example, of the child of divorce who sees his mother bring home a new sex partner — a man the child has never seen before, who then spends the night in the mother’s bedroom. Even if the man is not abusive, it’s still psychologically unsettling for the child to see a stranger enter into Mom’s most private space and then show up at the breakfast table.

I realize single parents may not want to hear that, but it’s worth asking people who grew up in that kind of environment how it affected them. Certainly, when a child’s mother has a man stay over who is not the child’s father, the child is at greater risk of abuse, statistically speaking. In this respect, it’s important to note that childhood sexual abuse does not only include physical abuse. It also includes sex talk and sexual inappropriateness — intentionally causing the child to take in something that he or she is too young to process, like social nudity or films with sexual content.

In the book you recount a beautiful moment in which you read a line from G.K. Chesterton and wanted more than anything in the world to experience “the poetry of not being sick.” Have you found that?

Yes. In Christ I have found that poetry that I was seeking.

However, it is always important to emphasize that our life in Christ is a journey, one that is not completed until we, Lord willing, arrive face-to-face with God. In talking about “healing sexual wounds with the help of the saints,” I by no means intend to canonize myself. My journey is still at its beginning. But each of us, through our baptism, has been given a message to share to lead others to Christ. I hope that by telling my story as an adult victim of childhood sexual abuse I might point others to the love of Christ by sharing my own journey of going from darkness into light.

Jennifer posted a second part of the interview on her blog Conversion Diary. I am reposting it here:

For many of you, Dawn Eden needs no introduction. She’s a popular blogger, a former rock journalist, Catholic convert, and author of the bestselling book The Thrill of the Chaste. I recently had the honor of interviewing her for the National Catholic Register, where she spoke for the first time publicly about her own experience as a victim of childhood sexual abuse. When I talked with her for that interview, I was overwhelmed by the amount of wisdom Dawn has gained on the subjects of healing and forgiveness. It was immediately clear that there was far more material here than could be contained in one interview.

So I wanted to share with you an informal Part II to our interview, in which Dawn speaks candidly on the subject of forgiveness — particularly forgiveness when you’ve been deeply hurt. The insights she’s gained through her healing journey carry powerful lessons for everyone, and so I am thrilled to share them here. And be sure to check out her brand new book, My Peace I Give You, which deals with these same subjects. Like with these interviews, I believe that the book contains powerful lessons for anyone who’s in need of healing and a deeper understanding of forgiveness.

***

Q: A central concept of your book is how to go about forgiving the unforgivable. In particular, you mention a quote from St. Josephine Bakhita in which she says that if she could meet the people who kidnapped and tortured her she would kiss their hands, because that was part of her journey to Christ. Do we all have to forgive in that same way?

Though we are all called to be saints, in daily life there may be many things that the canonized saints did that we are not called to do. With regard to Bakhita, what each of us is called to do is what’s within the Lord’s Prayer: to forgive, but not necessarily to reconcile.

In ministering to victims of abuse, we need to be very clear about the distinction between forgiveness and reconciliation. Many victims are under the mistaken impression that they are remaining in sin unless they reconcile with the abuser, but that’s not true.

Yes, we have to forgive. To forgive someone is to want God’s best for them. Thankfully, we don’t have to do the heavy lifting: all forgiveness comes from the Holy Spirit. When we forgive someone we ask the Holy Spirit to enter into us and forgive that person on our behalf, and we set our will on cooperating with the Spirit’s act of forgiveness.

Q: So there may be cases where people forgive, but don’t reconcile?

Ideally, forgiveness leads to reconciliation. But, unlike forgiveness, reconciliation is a two-way street. If someone is still abusive, the most loving and forgiving thing may be to not attempt reconciliation, inasmuch as having further contact with that person would only give him or her the opportunity to abuse again.

Q: How has this understanding of forgiveness helped you in your own journey of healing?

It is very freeing. No longer do I have to worry about whether I’ve worked hard enough to forgive. I just have to ask the Holy Spirit to work forgiveness in and through me. Then I need to trust that, with my having made the choice to forgive, the Holy Spirit will continue to work in me, taking the wounds that remain and join them to the wounds of Christ.Q: You mention that it is good for abuse victims to pray for those who have harmed them, but acknowledge that doing so may be impossible without stirring up up painful memories. What do you recommend for those kinds of situations?

I once got a very helpful tip from a Sister of Life. I was talking to her about how I felt that I owed it to God to pray for a certain person, but that it was painful for me to think about this person. The sister advised me to commend this person to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, to say to Mary, “Please place this person inside your Immaculate Heart, so that every time I’m praying for the intentions of your Immaculate Heart, I am praying for him.”

Q: That must help channel your negative energy toward that person in a more positive direction.

You know that Twilight Zone episode where there’s a child who has a dark supernatural power, and uses it to cast anyone who crosses him out into a cornfield? He casts out anyone with whom he’s angry, sending more and more people away to this place, which is an allegory for hell.

I think many of us do that in our minds sometimes, cast people away, send them to hell in our thoughts. To place them instead into the Immaculate Heart of Mary is a positive counter to that attitude. In both cases, you’re removing those people from the foreground of your thoughts — but, through Mary, you’re able to wish them into a good and holy place.

Q: Those of us who are longtime fans of your writing notice a change in your topics and tone: You used to be known for getting into heated debates with secular feminists, but you don’t do that anymore. Did this journey of healing have anything to do with that?

Yes. There was one event in particular that led me to reconsider the way I’d been acting out against feminist bloggers:

I discuss this in more detail in the book, but there was a time several years ago when I antagonized feminist bloggers, because I saw them as encouraging the same kind of attitudes that fostered my childhood sexual abuse. Though I make no apologize for proclaiming those truths about human life and dignity that the Church proclaims to be true, it was wrong of me to lash out in uncharity.

A turning point came after a woman named Zuzu began a series of blog posts reviewing The Thrill of the Chaste at the blog Feministe. She was picking and choosing things to insult me about, setting out to thoroughly shame and embarrass me, making fun of me in the most uncharitable way.

At first I just wrote her off as a mean-spirited person. Then one day I saw a blog entry of hers about her childhood, in which she talked about the difficult aspects of her relationship with her mother. She gave specific examples of her mother transgressing certain boundaries, and while they weren’t acts of sexual abuse, learning about them made me have so much compassion for her. I realized that it was a shame that I had burned so many bridges, and therefore couldn’t reach out to Zuzu and say, “I know how you feel.”

It was a point of conversion of heart for me, which led me to seek to avoid vitriol and uncharity in my public witness.Q: What would you say to someone who feels trapped by old wounds, not sure where to even begin down the path of forgiveness?

I recommend partaking of the Sacrament of Reconciliation. That may sound strange, because certainly those who have been abused have no reason to confess things done to them that was not my fault. But, as I write in in My Peace I Give You, although the primary reason we go to Confession is to be forgiven our sins, forgiveness is not the only thing that happens in that sacrament. Christ touches us, and, whenever He touches us, He gives grace.

A problem that many abuse victims have is anxiety caused by their uncertainty over the state of their soul. They have so absorbed the lies imprinted upon them by their abuse that they have trouble discerning the difference between the lingering effects of the sins committed against them, for which they are not responsible, and their own sins, for which they are responsible.

Recently a friend who suffered from this painful uncertainty asked me for advice on confession. I recommended to her that when she went to confess, having the priest the sins that she was certain were her responsibility, she should add, “Since Jesus is with me in this sacrament, I want to ask His healing grace while I am here, because I was abused when I was a child. I know I am not responsible for my abuse, but it has led to my having thoughts that distance me from Him. If any of those thoughts are sinful, I am very sorry, because I don’t want anything to separate me from Him. And even if they are not sinful, I ask Jesus to cover me with His Precious Blood and heal my hidden wounds.”

A few months after suggesting that approach to my friend, I went into the confessional and was moved to say the very words I had recommended. It was very powerful. Afterwards, I could not believe it had taken me so long to take my own advice.

* * *

For anyone reading this who has suffered sexual abuse, you are especially in my prayers. May God’s grace bring you healing, comfort and peace.

To learn more about Dawn Eden, visit her blog DawnEden.blogspot.com.

To learn more about Jennifer Fulwiler, visit her blog ConversionDiary.com.

PS – You can follow RoL on Bloglovin, Feedly or another news feed. If you are a social media fan like me, we can stay in touch through Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, GoodReads Letterboxd, Spotify or Instagram. 😉

PPS – This post may contain affiliate links.